|

This month, the Western Electric 394-W is once again playing a leading role. To celebrate 100 years of electrical recording of sound, I organized a session on April 2nd, using my 100-year-old Western Electric 394-W condenser microphone and vintage recording equipment, in the vintage Artone Studio, in Haarlem.

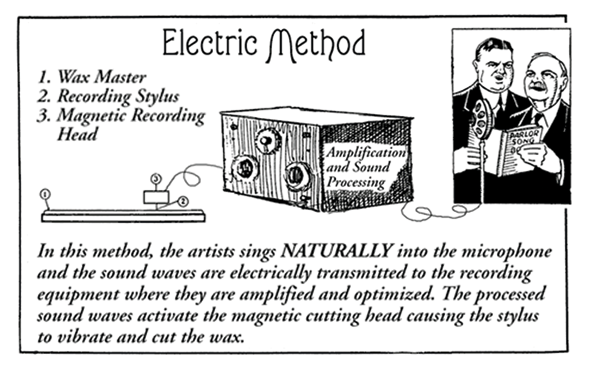

In 1925, Western Electric released equipment for electrical sound recording. The complete set consisted of a WE 394-W microphone, Western Electric amplifiers and a WE cutting head. The recording lathe was made by Scully, who had had previously made lathes for acoustic recordings. The sound was recorded on wax-coated records.

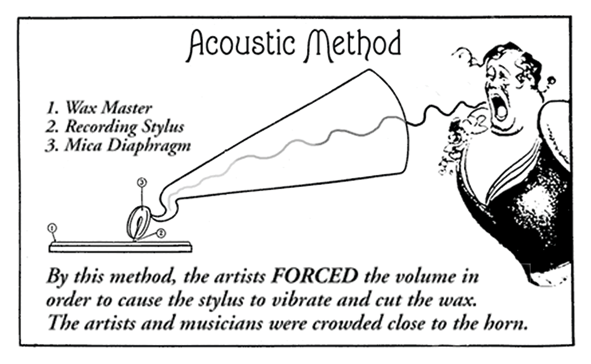

Electrical recordings had a much wider frequency range; 60-5000Hz. Acoustic recordings just had a range of 200-2400Hz, and only loud instruments and vocals could be recorded. As a complete recording set, the equipment was leased by Western Electric, under the name 'Westrex', to record companies Victor and Columbia. Both companies had to dig deep into their pockets, they had to pay $50,000 in advance each (now $760,000) and variable royalties per record of approximately $0.01.

The system was also offered to film companies, the recorded records could be played synchronously with films. Warner Brothers was the only film company at the time that dared to produce sound films, in the United States. In 1927, Warner Brothers would release the first synchronous sound film: 'The Jazz Singer'. Although only 291 words were spoken in the entire film, it was a resounding success, and the other film companies quickly followed.

The Artone studio has vintage Westrex amplifiers and cutting head and a Scully lathe, so the equipment comes close to what was used in 1925, for the first electrical recordings.

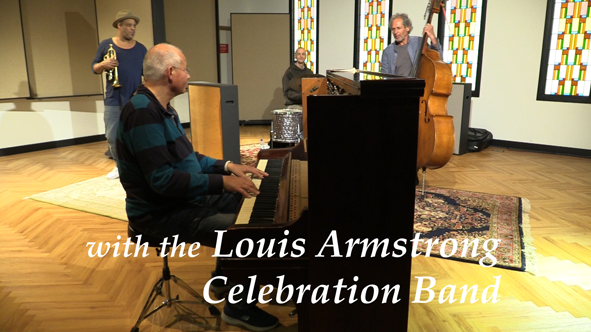

Because I wanted to record music from 1925, I was lucky that the renowned jazz musicians of the 'Louis Armstrong Celebration Band' were happy to participate in the recordings. Trumpeter and singer Michael Varekamp, pianist Harry Kanters, drummer Erik Kooger and bassist Harry Emmery, have years of experience with performances at home and abroad and many recording sessions to their credit, but this session was still special. Not only because of the old equipment, but especially because just one microphone was used. As a result, the sound balance had to be made in advance, it could not be changed afterwards. It meant that the volume that the musicians produced determined their distance to the microphone. During the recording in the studio, the distances were optimized; Michael Varekamp's trumpet turned out to be the loudest, so he was given a place furthest away from the microphone. Drummer Erik sat further forward, pianist Harry even closer and bassist Harry stood closest to the microphone. With the acoustic recordings before 1925 it was impossible to record a double bass properly, the instrument did not produce enough volume and was therefore replaced by a tuba.

Because Michael Varekamp also took care of the vocals, he had to walk up to the microphone for his vocals to be recorded properly.

This way the mix was determined in advance, nowadays it is always done after the recordings are finished, and a mix can take weeks.

The recordings were made direct-to-disc, the music was cut directly into the grooves, so everyone had to play the numbers exactly right, so as not to spoil the recordings; one mistake meant the end of the recording. Fortunately, this was no problem with these musicians, they always played accurately and without mistakes and in a few hours a total of five numbers were recorded.

The recordings were later digitalized. At that time, a durable matrix was made from the recorded wax master, from which records were then pressed. In this case, it wasn't necessary, but the excellent sound quality of the recording can be heard in the video clip. This is what a new record sounded like in 1925, without the scratches and clicks that would detoriorate the sound after a few plays.

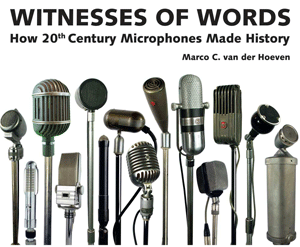

Many more types feature in my book Witnesses of Words. More information about that can be found at www.witnessesofwords.com

|

|

Video's

Video's Contact

Contact